How to Teach Phonemic Awareness

Learn how to make phonemic awareness activities a fun and exciting lesson plan for your students in our latest blog post.

In Equipped for Reading Success, Dr. David Kilpatrick emphasizes the far-reaching effects of reading on academics, behavior, self-confidence, and future opportunities.

He notes that “rarely do weak readers catch up.” According to research, many reading challenges can be prevented, and if educators are able to recognize the critical skills that build a strong foundation from the start struggling readers are capable of making more significant progress.

One of these critical skills and a strong predictor of future reading success is phonemic awareness. It’s an area of essential skill development that deserves our full attention. To better understand the importance of this skill, Kilpatrick looks to the overarching goal of reading: comprehension.

Skilled readers are fluent readers. They can focus on what they are reading because they have developed the ability to recognize words automatically. Unlike struggling readers, skilled readers are not faced with the laborious process of sounding out words or guessing. Regular and irregular words are distinguished effortlessly, known as “sight words.” How is this possible? Skilled readers store words through a process called orthographic mapping.

Orthographic mapping is an active and instant recognition process that allows us to see a word and instantly map the parts of the whole. The process does not occur in a left-to-right progression but rather as a string of letters in a unit.

When we map, we recognize, discriminate, and activate meaning all at once. Our brain retrieves this information from stored “files” that have developed over time and exposure and begin in early childhood with phonological awareness.

What Is Phonemic Awareness?

Phonemic awareness is the awareness that words are composed of sounds, and those sounds have distinct articulatory features. People with dyslexia lack the basic phonemic awareness that most individuals have, and they may have a hard time with reading comprehension, spelling, writing, vocabulary, and fluency.

Structured Literacy utilizes the Orton-Gillingham approach along with other structures such as phonemic awareness, morphology, orthography, semantics, syntax, and text structure to improve reading skills.

Consider phonemic awareness an umbrella term that describes three essential skill levels that are the foundation for reading: syllable level, onset-rime level, and phoneme level.

- Syllable Level – Teaching students to hear the parts of the whole word and identify them as syllables will assist with syllable division and decoding multisyllabic words in reading.

- Onset-Rime Level – Activities can expose students to word families and practice the segmentation of the onset (initial phonological unit before the vowel) and the rime (a string of letters that follow). Examples are p-an, s-at, st-all.

- Phoneme Level – Children acquire phonemic awareness when they can identify beginning sounds in words, blend sounds to make a word, and count the individual sounds within a word.

Students who do not develop phonemic awareness skills are at risk of struggling with reading in their future years. The Orton-Gillingham approach is made up of components that ensure that students are not only able to use learned strategies, but can also explain the how and why of phonological strategies. Phonemic awareness is one of these components that all teachers should become familiar with and consider a critical skill for developing readers.

With Orton-Gillingham, students learn skills that become progressively more complex, usually beginning with instruction in phonics and phonemic awareness. Once students exhibit phonemic awareness, Orton-Gillingham based programs address which letters or groups of letters represent different phonemes and how those letters blend together to make simple words.

What Are Phonemes?

Phonemes are the smallest units in our spoken language that distinguish one word from another. Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate phonemes in a spoken word.

The Orton-Gillingham approach translates the spelling of sounds into phonemes. Structured Literacy is deeply rooted in phonemes and systematically introduces the letters or graphemes corresponding to each phoneme. Once students exhibit phonemic awareness, Orton-Gillingham based programs address which letters or groups of letters represent different phonemes and how those letters blend together to make simple words.

For example, a child can identify the phonemes in mad when he understands that there is a phoneme at the beginning, middle, and ending of the word that makes up the whole word and that each of these sounds can be manipulated individually. To support young readers, teachers should have a good understanding of the sequence of specific phonemic awareness tasks that will prepare students for success in reading.

Early, explicit, systematic instruction in phonemic awareness, like Orton-Gillingham, increases a child’s attending to sounds according to research. In grades K-2, teachers can make phonemic awareness activities a highly anticipated part of the daily schedule. Phonemic awareness activities should:

- Include enjoyable, enriching activities that provide opportunities for children to engage in language play,

- Provide multi-sensory exposures (10-20 minutes per day) using auditory, visual, and tactile learning modalities,

- Incorporate songs, chants, poetry, and rhymes to support metalinguistic awareness

- Use data to inform instruction, and

- Vary complexity for different learners.

Examples of Classroom Activities to Facilitate Phonemic Awareness

Nars from Mars (Rhyming)

This activity helps to model rhyme generation to students in the classroom. Make a puppet from a sock or paper bag and give the puppet antennae to represent “Nars”. When Nars visits the class from his planet, the students will help him learn the English language. As Nars approaches various objects in the classroom, he will identify them incorrectly by rhyming. For example, when Nars selects a book, he will label it as a “nook,” a pen as a “chen,” a table as a “lable,” and so on. Each time, the students will help him by stating the correct (rhyming) word. Students will look forward to visits from Nars.

Going to Grandma’s (Rhyming)

Have the students sit in a circle on the floor and get ready to pack a basket full of rhymes to take to Grandma’s house. The teacher will start the string of rhymes by saying, “We are going to Grandma’s, and I am packing a ________.” The basket will be passed to the next student, who will say, “We are going to Grandma’s, and I am packing a (word that rhymes with the former word).” As an example, if the teacher said “skirt,” then the next student might add “shirt,” and then “dirt,” and so on. This will leave the students in giggles, and the round will end when no other rhyming words can be generated. The basket can get passed again with a new starter word.

1, 2, 3, 4 Syllables are on the Floor (Syllable Counting)

Place four hula-hoops on the floor and place a number 1, 2, 3, or 4 in each hoop. Place various objects in a box and model the first turn. Take the object and label it (example = elephant). Clap the syllables in the word and place the object in the hoop marked with a 3.

Sort the Sound (Phoneme Categorization)

Using sets of four pictures (or objects) per sound, the teacher will model how to complete the sound sort. If the target ending sound is /t/, the teacher will name each picture and select the three pictures in the set that ends with /t/ while removing the one picture that does not fit. This activity may be done with beginning, medial, or ending sounds.

Sound Boxes (Phoneme Segmenting and Blending)

The teacher will provide students with tokens (cubes, chips, stickers) and a sound box template. The child will listen to a spoken word and move a token to represent each sound. For example, if the teacher dictates the word “step,” the student will move four tokens, one for each individual phoneme /s/-/t/-/e/-/p/.

Stretching or Repeating (Phoneme Deletion and Substitution)

The teacher will dictate a word while stretching one of the sounds “/s/-/a/-/a/-/a/-/t/” and ask the student to identify the word. The student is then asked to replace the stretched sound /a/-/a/-/a/ with another sound /i/-/i/-/i/ and identify the new word. For phonemes that cannot be stretched, the teacher may repeat the target sound “/h/-/o/-/t/-/t/-/t/.” Once the student identifies the word, the teacher may have him replace the repeated ending sound /t/-/t/-/t/ with /p/-/p/-/p/ and state the new word.

Make a Change (Phoneme Manipulation-Deletion and Substitution)

The teacher will lead the class in a series of phoneme manipulation tasks, which will, in turn, activate the other phonemic awareness tasks. (From Kilpatrick’s book, Equipped for Reading Success)

- Say enter. Now say enter but don’t say ter. Student: en

- Say pin. Now say pin but don’t say /p/. Student: in

- Say smile. Now say smile but don’t say /s/. Student: mile

- Say club. Now say club but don’t say /l/. Student: cub

Kilpatrick hails phoneme manipulation tasks as superior to all other phonemic awareness tasks, as they require students to utilize other skills such as isolation, deletion, segmentation, and blending.

The Importance of Phonological Awareness Assessment

While phonological awareness skills are addressed in the Orton-Gillingham methodology, assessment data should be continuously monitored to effectively inform instruction, track progress, differentiate lessons, and identify students who may be at risk for future reading challenges.

The Phonological Awareness Screening Test (PAST), adapted and revised by Kilpatrick in 2018, can be used as a whole class screener or a component of a comprehensive, formal assessment. It evaluates a child’s understanding of the syllable, onset-rime, and phoneme levels using skills that develop in sequence from kindergarten to second grade.

Although this tool can be a powerful screener in the prevention of future reading challenges, it can also be used to identify older students who failed to develop these skills in earlier years. Regardless of age, the goal is for students to develop to the level of automaticity.

Orthographic mapping is a permanent storage system for written words that builds gradually and involves developing phonological awareness and word-level reading skills. This skill can be built up by utilizing the Orton-Gillingham methodology.

Simply put, when you can read a word instantly without putting any effort into decoding it, you know that word has been orthographically mapped into your brain’s storage system. This way, the ability to store words makes reading seem magical because it means we can listen to the story with our eyes and escape into the world of a great book.

What Is Orthographic Mapping?

In the early stages, listening to children read can be frustrating for an adult. Young readers approach words letter by letter, sounding out each with varying degrees of accuracy. Thankfully over time, reading skills improve, and children become more fluent. But how do they move from slowly decoding word by word to being able to read words quickly and easily? Thank orthographic mapping, the process competent readers use to store written words, so they can automatically recognize them on sight. The more words we have stored in this sight word bank, the easier reading becomes, allowing our brains to focus on comprehension rather than decoding because the words simply jump off the page and can’t be stopped.

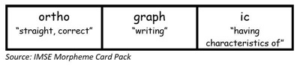

Oral language comprehension provides the foundation for understanding written text. The term “orthographic” comes from Greek, meaning to have correct writing. This mapping process makes a connection between the correct spelling sequences and the words we know. To understand the relationship, let’s look at brain processes used in learning to read.

Learning to Read is Complex

Learning to read is a complex process that involves connecting spoken language to the written code through four different processing systems in the brain. This Four-Part Processing Model (Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989) includes the phonological processor, a mental dictionary that stores all the words we’ve heard and use orally, which is utilized for sounding out the words we see. These words are taken in through the orthographic processor, and then we use our meaning and context processors to make sense of the text. For example, when a child sees the word “bat,” they can say the sounds /b/-/ă/-/t/ and determine the word’s pronunciation if it is in their phonological dictionary. But is it an animal or sports equipment? Putting the word into context allows the correct meaning to be established.

Speaking comes naturally for most children, and words learned along the way are stored for fast, easy retrieval in that phonological processor. Within those words are units of sound called phonemes, the smallest speech sound differences that are important for word recognition. Phonemes help us distinguish between “save” and “safe” – You can save for a rainy day, but money should be stored in a safe place. Although phoneme sequences are stored in the brain along with the words, unlocking them is not intuitive. Yet phoneme awareness is key to reading success because it’s needed for orthographic mapping.

Unlike speaking, reading is not a natural process and must be taught. English is an alphabetic writing system where the letters represent the speech sounds. Most children need instruction in the connection between the letters and the phonemes, and for many, this link needs to be explicitly taught. But the connection is not simply one letter to one speech sound. There are about 44 speech sounds in English, and our alphabet only has 26 letters, so we end up with letter combinations like ‘ch’ and ‘sh’ to spell words like ‘chip’ and ‘ship.’ English is also morpho-phonemic, meaning that spellings represent both sound and meaning. For example, ‘people’ and ‘population’ are related in meaning, and although the ‘o’ isn’t sounded in ‘people,’ it is there to mark that connection.

These types of irregularities in spelling are not a problem for reading once our brains become skilled at orthographic mapping. We aren’t born with this orthographic mapping system; our brains need to be taught how to do it. The sounds or phonemes become connected to the letter sequences in a word. They are permanently bonded and stored for instant access after one to four exposures in typically developing readers. The words stored in our phonological memory bank, which are built up naturally as we learn to speak, attach to the printed letter sequences by orthographically mapping them together. Once the system is started, our brains learn to do this automatically when we encounter new words. But how do we get this system started?

What Do We Need for Orthographic Mapping?

To become good at orthographic mapping, children need to develop phonological awareness and word-level reading skills. Learning to read requires that children understand the alphabetic principle, that words are made of sounds and can be written with the letters of the alphabet. To do this, they need an awareness of the phonemes in spoken words and proficiency in using phonics to decode words. This involves using the four processing systems: phonological, orthographic, meaning, and context when needed for word meaning.

Phonological skills build along a continuum. Early skill development begins with larger sound chunks in words, such as being able to rhyme and segment syllables. Next, individual sounds can be noticed in shorter words, starting with the first sound, then the last, and finally the middle sound. Once children develop basic phoneme awareness, they can learn to blend and segment words for reading and writing. This process paves the way for our brain to learn that ALL the words stored in our phonological dictionary can be broken apart this way, which is critical for permanent written word storage. The phonemes in spoken words become the metaphorical glue that attaches to the written representations. But children need other tools to develop word reading skills that lead to orthographic mapping.

As early phonological skills develop, children need to learn letter names and basic letter sounds. Learning that letters are used to write the phonemes will open the door to decoding words for reading. In our example with the word ‘bat,’ knowing that these letters represent the sounds /b-ă-t/ allows the connection to be made to this word that is already stored in our phonological dictionary. The reverse can be done for encoding, or spelling, to write words. As more letter-sound relationships are learned, more words can be unlocked.

Practice Makes Automatic

The more practice our brains get with this sound-symbol relationship pattern, the more automatic the process becomes. One key to the orthographic mapping of words into our permanent memory system is the proficiency with which we have access to the phonemes in spoken words. Children can sharpen this skill through phoneme manipulation practice, such as saying the word ‘bat’ and then repeating it but changing the /b/ to /m/ for ‘mat.’ A more advanced version of this practice would be to say ‘slip’ then repeat it without the /l/ sound, ‘sip.’ The ability to do this type of wordplay makes the phonological processer stickier and better able to attach to text.

Phonics is essential to reading and is best learned when explicitly taught. Proficiency with letter-sound relationships is another key to orthographic mapping. Beyond basic letter sounds, good phonics instruction should include common spelling rules and patterns in English along with basic syllable types.

The ability to decode a word with phonics knowledge provides children with the skills to unlock new words they encounter. This knowledge helps children become familiar with the allowable letter sequences that make up words. Only one to four exposures are needed for typically developing readers before a word’s spelling is locked together and permanently stored for instant recognition.

Although listening to children learn to read by painstakingly decoding each word can be tedious, it is precisely this process that makes orthographic mapping possible. It is the combination of phonemes and phonics that begins to build the orthographic mapping storage system. Once activated, reading begins to transition into the magical process of making the words on the page speak. This opens the door to new worlds.

In the 1930s, neuropsychiatrist and pathologist Dr. Samuel T. Orton and educator, psychologist Anna Gillingham developed the Orton-Gillingham approach to reading instruction for students with “word-blindness,” which would later become known as dyslexia. Their approach combined direct, multi-sensory teaching strategies paired with systematic, sequential lessons focused on phonics.

Orton-Gillingham is a step-by-step learning process involving letters and sounds that encourages students to advance upon each smaller manageable skill learned throughout the process. It was the first approach to use explicit, direct, sequential, systematic, multi-sensory instruction to teach reading, which is effective for all students and essential for teaching students with dyslexia. Today, the Orton-Gillingham approach is used around the world to help students at all levels learn to read.

Critical Components of the Orton-Gillingham Approach

- Multi-Sensory – The teaching of new concepts incorporates visual, auditory, and kinesthetic pathways. With this approach, students learn language by ear (listening), mouth (speaking), eyes (seeing), and hand (writing).

- Structured, sequential, and cumulative – Through direct, explicit instruction, it progresses logically at the primary level and progresses to more advanced concepts that build upon the previous skill learned, with practice and review.

- Flexible – Through assessment, differentiation, and grouping, teachers can instruct students based on their needs.

- Language-based – Directly teaches the fundamental structure of language, starting with sound/symbol relationships and progressing to more complex concepts such as higher-level spelling rules and Greek and Latin Bases.

The Key Benefits of the Orton-Gillingham Approach

- Sequential – Lessons are presented in a logical, well-planned sequence. This sequence allows children to make easy connections between what they already know and what they are currently learning.

- Incremental – Each lesson builds carefully upon the previous lesson. This helps students move simple concepts to more complex ones, ensuring that there are no gaps in their learning.

- Cumulative – Through direct, explicit instruction, it progresses logically at the primary level and progresses to more advanced concepts that build upon the previous skill learned, with practice and review.

- Individualized – Anna Gillingham once said, “Go as fast as you can, but as slow as you must.” Curriculums that follow this approach make it easy to teach students based on their individual strengths.

- Phonograms-Based – By teaching the phonograms and the rules and patterns that spell the vast majority of English words, the Orton-Gillingham approach takes the guesswork out of reading and spelling.

- Explicit – Students are taught exactly what they need to know in a clear and straightforward manner. Students know what they are learning and why they’re learning it.

Where Orton-Gillingham Fits

While Orton-Gillingham has long been associated with dyslexia, teachers have been advocating for years that the Orton-Gillingham method be utilized in every classroom.

Orton-Gillingham places a strong emphasis on systematically teaching phonics so that students understand the how’s and why’s behind reading. Word recognition is best taught through a phonics-based approach, wherein students develop knowledge and skills about how the alphabet works to become expert decoders. Children can then apply the knowledge they learn to decode and encode new words.