What Is the Science of Reading?

The Science of Reading has demystified how we learn to read and offers evidence backed by science to confirm that there is one right way to teach reading.

Literacy is a fundamental human right connected to all learner’s future outcomes. A student’s entire education relies on whether or not they are a proficient reader. When it comes to literacy instruction, it is our educators who we depend upon to be well-equipped to take on such a significant task.

The Science of Reading is a large body of research on the science behind reading. This conclusive, empirically supported research provides us with the information to understand how we learn to read, what skills are involved, how they work together, and which parts of the brain are responsible for reading development.

This body of research encompasses years of scientific knowledge and shares contributions from experts and key stakeholders from relevant disciplines. These disciplines include, but are not limited to:

- Education

- Special Education

- Literacy

- Neurology

- Psychology

From this research, we can identify an evidence-based best practice for teaching reading: Structured Literacy.

Science of Reading expert David Kilpatrick stated, “We teach reading in different ways; they learn to read proficiently in only one way.” The Science of Reading provides evidence backed by the science of how we best learn to read.

The Science of Reading helps us understand the cognitive processes essential for reading proficiency. It describes the development of reading skills for both typical and atypical readers.

The Science of Reading and Orton-Gillingham

Orton-Gillingham is a long-standing, evidence-based multisensory instructional approach to teaching reading that is now reinforced by more modern research from the Science of Reading. Orton-Gillingham strongly emphasizes systematic, explicit, diagnostic phonics instruction so that students understand the hows and whys behind reading.

Reading difficulties are highly preventable for young, at-risk students if they are approached correctly. Studies demonstrate the efficacy of intensive phonics instruction, including phonemic awareness training, decoding strategies, and opportunities for repeated practice. Efficient orthographic mapping is achieved through intervention in these skills, ultimately leading to success.

Phonics empowers our students. By memorization of the sounds of just ten letters, students are able to read:

- 350 three-sound words

- 4,320 four-sound words

- 21,650 five-sound words

The Science of Reading illustrates that educators need to secure phonics as the primary approach to reading and, in turn, prepares students to become fluent and independent readers for life. The Science of Reading proves that we do not learn to read differently. With the help of Orton-Gillingham instruction, every student can access the same knowledge and skills to become a good reader.

Due to the complexity of teaching, one-third of teachers leave the profession within three years, and nearly half of them leave within five years, as found in a study by Ingersoll. All teachers, even the experienced ones, encounter new challenges each year, including:

- Changes in standards

- New instructional methods

- Advances in technology

- Changes in procedures

- The growing diversity of student learning needs

This reinforces the need for teachers to collaborate and engage with one another around meaningful topics in education and other supportive learning opportunities. It is no secret that not all teacher professional development opportunities are equal or effective. However, specific professional development characteristics are linked to long-lasting, positive outcomes for teachers and their students.

Unfortunately, most of the professional development opportunities out there are not up to par with the expectations of high-quality professional development. According to research, opportunities that are less in-depth are provided by administrators and districts to serve larger groups of educators within an allotted time and budget.

Teachers need professional development experiences that are more effective, sustained, and focused on promoting lasting change.

The term “andragogy” (similar to pedagogy) is referred to as adult learning and was developed by Malcolm Shepard Knowles. Knowles discovered adult experiences, whether positive or negative, are strong means for their learning. It was discovered that adults seek problem-centered information to be applied instantly to advance positive change in their work.

Gains outweigh associated costs when we fully recognize the outcomes of high-quality professional development. Three primary learning outcomes of professional development are:

- Based on their participation, teachers will benefit from the knowledge and skills learned

- Teachers improve their teaching practices by implementing what they learn

- As a result of the new content learned, student learning and performance improves

Specific characteristics that are identified and documented to foster successful learning further enhance the outcomes of students.

Effective Professional Development Criteria

Content-Based

Teachers should walk out of their professional development training with a new bag of tricks up their sleeves. Gaining explicit instruction of knowledge, skills, and strategies while improving the teacher’s existing content knowledge is the ultimate goal of professional development. Teachers should get back into their classrooms prepared to apply the information to lesson planning, assessment, and distinguished instruction. Content-based professional development will be aligned with statewide standards and assessments.

Relevant

Relevant learning is explicit, realistic, and challenging. When content is meaningful, and teachers can link it to their prior knowledge, teachers are motivated to learn. The content must be relevant to what is currently needed in their classroom.

Teachers feel more supported when professional development is directly related to the current needs and requirements of both teaching practices and their students.

Active

Teachers love inspiration, new ideas, and engaging ways to bring their classrooms to life. Hands-on opportunities to model and practice, engage in planning, review lessons, or watch live videos of implementation are what we call active learning.

Visual, auditory, and tactile-kinesthetic modalities are activated in multi-sensory Orton-Gillingham learning. This engages and challenges all learners, children, and adults alike! Teachers should experience the methods they will deliver to their students while taking part in professional development opportunities.

Teachers should be given multiple opportunities to seek clarification, process information, raise concerns and ask questions with peers and expert trainers in professional development that spans days or weeks.

Collaborative

Effective professional development should be collaborative and provide opportunities for collective participation between teachers, leaders, and experts. This quality experience allows teachers to share their strategies and knowledge with others in the same grade, department, or school. It improves troubleshooting and focuses on progress. Teachers can leave this type of high-quality learning energized and inspired.

Administrators can magnify the benefits of effective professional development if they provide it to multiple cohorts within the school. Educators across all sectors develop a common language, and student needs are targeted through thoughtful shifts in instructional delivery.

Empowering

Engaging teachers in professional development that is directly aligned with their school’s mission and philosophy gives them a sense of urgency to bring this new knowledge into practice within their classrooms.

Opportunities for communication that promotes value, inquiry, uncertainty and builds teacher confidence is supported through professional learning communities. Students take notice when teachers return to the classroom with new activities, ideas, strategies, and engagements.

Leaders, too, should engage with their educators who have taken part in professional development and ask questions and provide encouragement. Teachers who take part in uplifting professional development training are always open to sharing their enthusiasm.

Sustainable

Teachers should consider an ongoing commitment to professional development that is specific and deeply focused on their specific subject. This ongoing commitment allows educators to translate ideas into practice effectively. This allows the teacher to build upon their knowledge and experiences over time and potentially gain specialist knowledge in their highest area of need.

Sustainable learning is an ongoing process that spans weeks, months, and even years. This includes workshops and classes, practicum or internships, and even certification programs.

Supported

To master a new skill, it takes roughly 20 trials of delivery.

When teachers are provided ongoing expert support and feedback post-professional development, it allows time to troubleshoot and contend with implementation challenges within the classroom. This opens opportunities for teachers to benefit from constructive feedback, assessment, and observation to improve delivery, practice, and long-term outcomes.

In Conclusion

It is no secret that effective professional development proves to improve instructional practices. Education leaders should always consider teacher choice when choosing effective professional development that can positively impact teaching culture in the classroom, grade, department, or entire school.

The most important result of effective professional development is how students improve. When teachers learn, students learn.

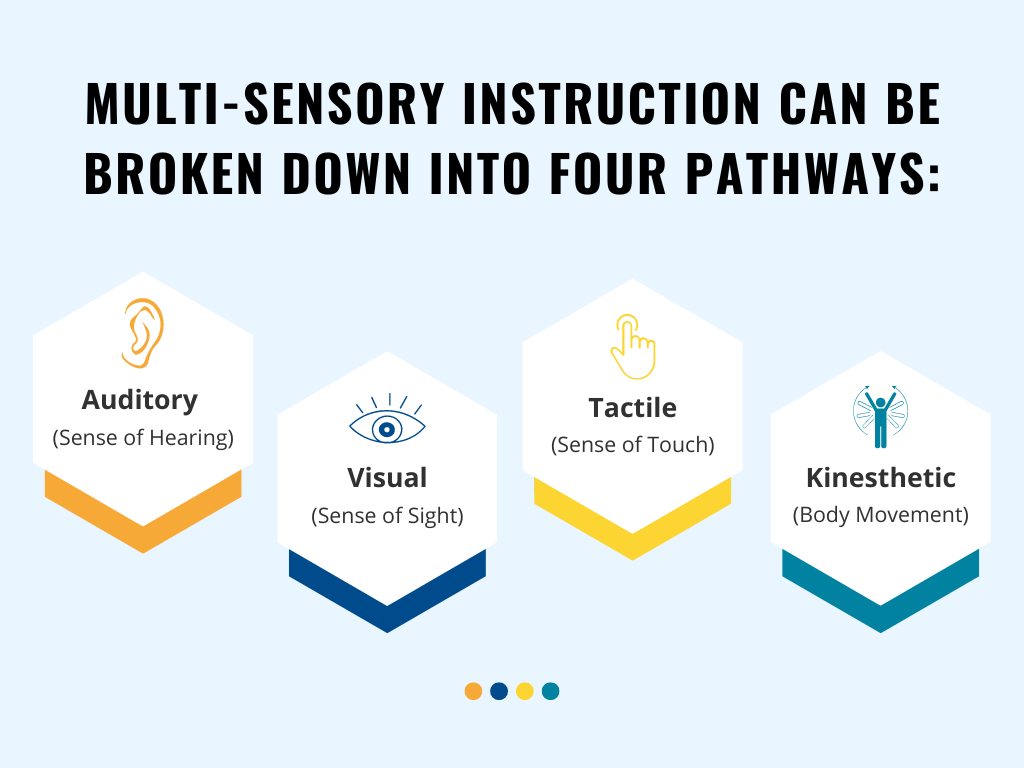

For every student, one of the modalities mentioned in the image above is usually predominant. Some students may prefer to see a visual representation of an image to grasp it, while others may choose to use their hands.

According to Dr. Samuel Orton’s research, brain dominance significantly impacts learning to read. Both hemispheres of the brain act and react, think and process, and solve problems in their own specific and quite different ways, and one side is usually dominant.

A student can capitalize on their strengths and strengthen their weaknesses when all four learning pathways are utilized within a lesson. Educators also have a higher chance of students grasping the concept during initial instruction.

Many believe the Orton-Gillingham approach is only beneficial in special education or reading intervention, but that is just not the case. Orton-Gillingham is for all students.

Multisensory Orton-Gillingham Activities

Every student learns at their own pace, but when multisensory (also known as multimodal) strategies are utilized, students are given the opportunity to reach their full potential through various delivery styles.

Check out these five activities that you can begin using in your classroom today!

Read it, Build it, Write it

Consider using this Orton-Gillingham activity when teaching Red Words or irregular words (i.e. ‘does’ or ‘was’). Students need to be able to master these words that do not fit the expected spelling patterns.

Start by giving each student a sheet of paper with three boxes on it with the labels “Read It,” “Build It,” and “Write It.” Additionally, you should provide your students with Red Word flashcards, block or magnetic letters, and a pencil or crayon.

Read the irregular words in the “Read It” box aloud with your students. Students are then asked to identify what makes the word irregular and what is unexpected in the spelling pattern. Students should then use the block or magnetic letters to build out the word in the “Build It” box. Once they successfully build it out, the students should write it in the “Write It” box.

Writing in Shaving Cream or Sand

This Orton-Gillingham activity utilizes visual, auditory, and tactile (fine motor) pathways. Take a plastic tray, cookie sheet, tabletop, or other medium and cover them with shaving cream or sand. Call out a known sound and have your students repeat the sound. Then they should use their fingers to write the letter that makes that sound while verbalizing the letter name and sound (/d/ d says /d/). By utilizing their fingers to write the letter, they are accessing thousands of nerve endings that transfer patterns to the brain.

You can also use this strategy for whole words, but be sure they are phonetic words that follow expected spelling patterns.

Writing in the Air

This Orton-Gillingham activity is similar to the shaving cream or sand activity but instead uses kinesthetic (gross motor) pathways. Utilize muscle memory to reinforce the letter and sound each letter makes through air writing.

Your students should use their dominant arm for this activity and move from the shoulder to promote large muscle movement. As the students write the letter in the air, have them visualize it in a specific color while verbalizing the letter name and sound.

Arm Tapping

This Orton-Gillingham activity helps students master irregular words through multisensory review.

Start this activity with a stack of cards containing the words your students are learning. State the words one by one while holding the card, with your non-dominant hand, in front of you. Ensure your students can see the word by making sure the card is at eye level with them.

Have students tap left to right using their dominant hand. Right-handed students start with their right hand on their left shoulder, and left-handed students start with their left hand on their right wrist. State each letter of the word while your students tap down their arms, and once they tap out each letter, state the whole word while creating a sweeping motion down the arm. Think of this sweeping motion as underlining the word.

Blending Boards

Blending boards can be used to prepare students for decoding multisyllabic words. Blending boards help with the practice of segmenting sounds and blending those sounds into syllables.

Take phoneme cards and place them in CVC (consonant vowel consonant) order on the blending board. Place your hand over each card while your students sound them out, and once they state each sound, sweep your hands across the board and have your students state the word or syllable.

You can use VC patterns or start with a continuant sound versus a stopped sound with students who struggle.

Additional Resources

Bringing Orton-Gillingham strategies into your classroom creates endless opportunities for your students. For more insights and strategies, visit the links below:

- Search “Orton-Gillingham Activities” or “Multi-sensory Activities” on Pinterest to find hundreds of exciting ideas you can implement in your classroom immediately.

- Check out the IMSE YouTube Channel, where you’ll find several helpful videos about teaching open and closed syllables, three-part writing drills, and more!

What Is Dyslexia?

According to The International Dyslexia Association (IDA), “Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.”

The cause of dyslexia is still unclear, but we know that there are differences in brain development and function between those who have dyslexia and those that don’t.

According to The Reading Well, approximately fifteen percent of people have dyslexia. They also state that “between 25-40% of children with dyslexia also have ADHD, and conversely, approximately 25% of children with ADHD also have dyslexia.”

Many children who struggle with dyslexia are unidentified and left to tackle significant challenges in reading, spelling, and writing without interventions.

What Are the Early Symptoms of Dyslexia?

In the preschool through second-grade years, many children are in the process of “learning to read.” From third grade on, students are shifted into a “reading to learn” approach. When students make that shift, they are then expected to apply automatic and accurate decoding strategies to read with improved fluency.

Around this age is when dyslexia proves to be most evident. Students begin to showcase signs of frustration or a lost desire to read as they are unable to keep up with their classmates.

Patterning is how the brain learns. Patterns and rules for spelling that many were explicitly taught include:

i before e except after c…

two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking…

These rules forge patterns for reading and spelling between familiar and unfamiliar words. Many other rules like these exist but are rarely taught because most students do not need direct, explicit instruction to become efficient readers.

However, students with dyslexia and other language-based learning disabilities need that direct, explicit instruction, like Orton-Gillingham, to understand the irregularities that exist in the complex English language.

For at-risk students, it is important to frequently screen and assess them for reading problems. If a student is showing signs of reading difficulty, screening and assessment will help to recommend appropriate strategies to prevent further reading gaps from developing.

Dyslexia Symptoms to Look Out for in Preschool

- Delayed speech

- Chronic ear infections

- Difficulty pronouncing words

- Confusion with following directions

- Mixing the sounds and syllables in long words

- Difficulty learning the names of colors or shapes

- Trouble reciting the alphabet

- Difficulty with rhyming

- A family member with dyslexia

Dyslexia Symptoms to Look for in Elementary and Middle School

- Frequent spelling mistakes

- Letter or number reversals after first grade

- Slow, choppy reading

- Guessing after repeated exposure to letters or words

- Poor comprehension

- Poor memory for sight words (e.g. they, were, does)

- Difficulty following instructions with multiple steps

- Trouble memorizing math facts

Universal screening for dyslexia helps to prevent the advancement of reading difficulties associated with unknown reading disabilities. Evidence-based reading interventions, such as Orton-Gillingham, can better prepare students to confront reading at the word, sentence, and passage levels.

Screening should begin as soon as preschool and should address the developmental skills of phonological awareness, letter-sound association, blending, word recognition fluency, word identification, vocabulary, oral reading fluency, and comprehension.

Below is a list of resources for universal screening and curriculum-based measurement tools:

- https://dyslexiaida.org/universal-screening-k-2-reading

- https://dibels.uoregon.edu/

- https://www.nessy.com/us/screening-for-dyslexia/

- https://learningally.org/Dyslexia/Dyslexia-Test

- http://onlinepar.net/resources/about-the-par/

Universal screening results should be used to identify the right intervention and recommendations for a further professional evaluation. To ensure struggling readers are making adequate improvements and interventions are proving effective, progress monitoring should be conducted frequently.

Parents and educators must recognize the importance of universal screening and early intervention to support struggling readers. Students identified with dyslexia cannot thrive in a traditional education setting. They must be given the proper tools and techniques for reading.

Ways to Help Students with Dyslexia

Address the Issue

A thorough evaluation will help to identify areas of need in learning the five components to reading. Students who show symptoms of dyslexia benefit best from the Orton-Gillingham approach to reading. Research shows that the brain changes when consistent explicit, multisensory instruction is delivered.

Understand Individual Student Learning Styles

Promote a positive learning environment by understanding each individual student’s learning style, motivation, and interests. Students who struggle with dyslexia show signs of dominance in the right side of their brains. Incorporating imagination, art, visual memory, hands-on skills, music, and creativity can promote overall success.

The Orton-Gillingham Approach is Key

Stimulate visual, auditory, and kinesthetic-tactile senses to promote learning. You can do this by:

- Visual: have the student refer to memory anchors through writing, drawing, highlighting, and visual cues

- Auditory: provide repetitive input through reading aloud, singing, and chanting

- Kinesthetic-Tactile: utilize movement to reinforce formation and patterns, like tapping, acting out, and air-writing

Activate all of the senses simultaneously whenever possible.

Empower Students with the Right Tools

Identify appropriate accommodations and develop a plan that includes valuable benefits and support. Being able to independently manipulate and apply strategies is vital in building fluent reading skills. Text-to-speech, audiobooks, spellcheck, and more are some assistive technology tools that enhance the learning experience and alleviate stress and frustration.

Propose Enrichment Lessons

Students who struggle with dyslexia are bright, creative, and talented and should develop their talents through music, technology, art, sports, science, and more.

Read Aloud

Research reports that in the development of mirror neurons, children will mimic good reading and fluency skills if repeatedly exposed to them. Parents can positively influence their children by showcasing enthusiasm for reading at home.

The best first step in identifying students with dyslexia is through universal screening. A comprehensive diagnostic evaluation should be conducted if problems continue despite initial intervention.

Screening and evaluation results can assist in developing an intervention plan that identifies the student’s needs, promote the implementation of approaches like Orton-Gillingham, and monitor progress yearly. Early identification leads to essential prevention and intervention to give the student the resources they need.

There has been a debate in the general education classroom between whole language instruction and phonics instruction for many years. And Orton-Gillingham was reserved for students identified with a reading disability.

The whole language approach to literacy assumes that students can expand their understanding of reading concepts and text through repeated exposure to rich children’s literature. While phonics, spelling, and decoding are addressed through word study, they are not systematically or explicitly taught.

Instead, the “three cueing system” is encouraged. This system promotes guessing based on semantics (context clues, pictures, background knowledge), syntax (use of language patterns), or graphophonic cues (sounding out words).

While context clues may sometimes prove to be a beneficial strategy in reading, Dr. David Kilpatrick reminds us that context helps identify the meaning of words but should not be promoted as an effective strategy for word identification (2015).

The use of phonics instruction faded away when the use of the whole language approach took root in elementary classrooms across the country. Over time, students began to rely more on compensatory strategies.

Unlike learning to speak, reading is not an innate ability. Students must receive instruction to achieve the skill of reading. When the need for phonics instruction arose again, users of the whole language approach blended phonics lessons with the cueing system to create “Balanced Literacy.”

While Balanced Literacy focused on opportunities for shared, guided, and independent reading, students continued to rely on the cueing system. Struggling readers fell behind while this approach emphasized using leveled reading books for independent reading practice.

When people became more aware of the rising number of students reading below grade level and advocacy for dyslexia intervention increased, “Structured Literacy” came to the forefront.

Structured Literacy is an umbrella term adopted by the International Dyslexia Association (IDA) that refers to programs such as Orton-Gillingham that teach reading based on the Science of Reading. Structured Literacy programs prove to be beneficial not only to the struggling reader but to all students.

Results of the 2019 report from the NAEP on nationwide student performance showed that 4-grade reading scores were lower than in 2017, with 38% reading at a “below basic” level. These statistics are exactly what prompted the IDA and other advocates of reading intervention to define what effective reading instruction is properly.

Structured Literacy provides a framework to incorporate the principles (how we should teach) and the elements (what we should teach).

How to Teach Structured Literacy

Teachers must have a strong knowledge of the principles of Structured Literacy.

Explicit

Teachers should give a direct and clear explanation for each new concept during explicit Orton-Gillingham instruction. Multi-sensory strategies should enhance learning and instruction through visual, auditory, and tactile/kinesthetic senses.

Teachers should provide guidance and feedback during student application to promote proper learning.

Systematic

Instruction should follow a well-defined scope and sequence that provides a logical advancement of skills that progress from simple to more complex.

Cumulative

New concepts are layered on top of previously learned concepts, and the foundation of phoneme-grapheme relationships, generalization of rules, and reliable spelling patterns is continuously reevaluated to build automaticity.

Diagnostic/Responsive

Progress monitoring allows teachers to identify and make decisions for prescriptive teaching and differentiation.

Gough and Tunmer’s Simple View of Reading can provide a snapshot of the two processes required for students to achieve reading comprehension through Structured Literacy. Those processes are decoding (word recognition) and language comprehension.

Dr. Hollis Scarborough’s well-referenced Reading Rope provides a research-based analogy that breaks these two processes into sub-processes and skills. These are woven together to clearly represent how these decoding skills and comprehension strategies are intertwined to lead to skilled reading.

What to Teach to Support Decoding

Phonemic Awareness

In 2000, the NICHD reported that over 90% of students who presented with significant reading problems exhibited a core deficit in their ability to process phonological information. This was especially evident at the phoneme level and identified phonemic awareness skills as a reliable predictor of future literacy learning. Teachers should expose students in preschool to oral exercises or listening activities that will improve awareness of the smallest parts of our spoken language, such as sounds and syllables. As they develop skills to hear and identify the parts, they can then progress through more advanced activities to strengthen their ability to manipulate sounds and syllables accurately and automatically.

Phonics

Explicit Orton-Gillingham instruction should be given to students in recognizing the sound-symbol correspondence. Students can progress to blending letter sounds sequentially from the sound to syllable to multi-syllabic word level in decoding when they learn that graphemes (letters) and letter combinations represent phonemes (sounds).

Orthography

The English language is made up of a complex structure of 26 letters that are represented by 44 sounds. Cumulative instruction that focuses on building letter and word patterns into memory to enhance spelling knowledge is beneficial for students. Students learn to identify syllable patterns and syllable types through Structured Literacy, which provides a strategy to break multi-syllabic words into syllables for easier decoding.

Morphology

Often recognized as prefixes, suffixes, roots, and combining forms, morphemes comprise significant parts of words. Morphological awareness begins early in the young child’s use of language and later provides a strategy for word-level reading, spelling, and vocabulary. The explicit, systematic, and sequential instruction of morphological knowledge that Orton-Gillingham provides will also prepare students to transition into third grade, where Latin and Greek-based roots are commonly presented in text.

What to Teach to Support Language Comprehension

Syntax

A student’s knowledge of the parts of speech is also predictive of reading comprehension. The structure of sentences becomes more complex across the grades. Students can easily get lost if unable to recognize concepts such as the use of connective words, pronoun referencing, clauses, agreements, and more.

Semantics

Repeated exposure to Tier 2 words and more sophisticated language used in teacher-read text is one way to advance student vocabulary development. In addition, students will benefit from learning strategies to enhance word meaning, including the use of application of synonyms, context clues, visualization, and lessons in figurative language.

Discourse

A student’s overall comprehension is highly impacted by their background knowledge. When teachers model metacognition during reading, comprehension will profit. Enhanced student engagement happens when skills such as predicting, questioning, inferencing, clarifying, and summarizing are modeled consistently. Teachers should weave opportunities to focus on cause/effect, compare/contrast, and various text structures.

Who Should Teach Structured Literacy?

With legislation constantly changing, teachers are seeking to be prepared to support Structured Literacy in their classrooms. They will need the broad knowledge found in the Knowledge and Practice Standards (KPS) that the International Dyslexia Association has developed in an effort to unify and certify those who teach reading in order to feel equipped to deliver this evidence-based approach.

By adopting Structured Literacy as an application of the Science of Reading, the International Dyslexia Association has provided a great service to teachers everywhere. Structured Literacy is an effective reading framework and is necessary to help students with language-based learning disabilities, and those in the general education classroom become successful and engaged learners.

Why Teach Structured Literacy?

The debate regarding effective instruction will end with Structured Literacy. As more and more teachers become skilled in Structured Literacy and more programs fall under the Structured Literacy umbrella, many significant changes will fall into place.

Teachers will be empowered to diagnostically teach and monitor students’ progress and be able to customize the experience for each individual student.

Structured Literacy can ensure that students are properly exposed to important foundational literacy skills that are sequential, systematic, and cumulative. This can alleviate the need for wide variations of reading approaches and provide a smooth transition to more advanced concepts every year.

This means that schools can engage a positive and collective impact on the number of students who can read at or above grade level in the future.

For many students, the solution to better reading comprehension is reading fluency.

A new audiobook is available for purchase, and you have the option to have Amazon’s Alexa™ read it or the author. Who would you choose, Alexa or the author, to guide you through the text, painting each phrase as a picture and detailed perspective of the story?

The difference between reading words and comprehension is reading fluency. While Alexa may successfully read most words accurately, considering the high capacity of word recognition, parts of the story will be lost, or the listener may lose interest due to the monotone cadence. Disrupted oral language comprehension is the result of the lack of adequate fluency. Therefore, linguistic comprehension is not reached. You would potentially become frustrated, not completely understand the story, or possibly give up entirely. Without fluency, reading comprehension – and the enjoyment of reading – is lost.

Fluency Is…

Fluency is the link between word recognition and reading comprehension, according to the National Institute for Literacy and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2006). To achieve reading comprehension, students must accurately recognize words and successfully process oral language, as illustrated in the Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986). Orton-Gillingham is just one method on how to achieve fluency.

Students must learn the basics of reading—to adjust their tone based on punctuation, learn to group words into phrases, and apply elements of prosody (intonation, stress, and pausing); before they are then free to focus on reading for understanding. “The essence of fluency is not reading speed or oral reading expression, but the ability to decode and comprehend at the same time (Rasinski, Ph.D., Blachowicz, Ph.D., & Lems, EdD, 2006).”

“Fluency can change, depending on what students are reading, familiarity with the words, and practice with reading text. Be aware, however, that just because a child is a fluent reader does not mean the child comprehends. Students may be reading words without thinking about or visualizing what they are reading. They may recognize words with automaticity and be successful at decoding, but are not reaching a deep level of comprehension (Jeup, 2020).”

Reading Fluently Through Orton-Gillingham Instruction Sounds Like…

“Please, Mommy, read to me in a robot voice again!” a boy (age 4) exclaimed. While the reader is reading as a robot character, fluent readers work hard to avoid robotic-sounding reading. Revisit the example of Amazon’s Alexa™. If asking Alexa a quick and simple question, the fluency of her speech typically does not impact the ability to understand the answer.

Similarly, a student’s fluency at the phrase level will not likely impact understanding, but no one is requesting Alexa to narrate a podcast series or audiobook. Therefore, while reading aloud, fluent readers should model how to decode and comprehend at the same time using appropriate fluency. This reinforces that reading aloud with children is extremely valuable.

Orton-Gillingham Instruction Can Help Students’ Fluency Improve by…

To develop the ability to read accurately and quickly with good expression, phrasing, and comprehension, teachers must model fluency for students. Teachers should read aloud to students, listen to students read, provide a wide variety of activities, and encourage parents to remain diligent when reading at home in order to hone these skills.

Read to students: When teachers read aloud, they model comprehension strategies, including predicting, questioning, clarifying, and summarizing, as well as fluency. Differentiating characters’ voices allows students to follow individual characters, and relaying the mood of the story with subtle changes to tone, cadence, and stress, children learn how to read for understanding. From this, students can learn to paint visual images based on the text and benefit from exposure to a more expansive vocabulary than they may presently access during independent reading. It’s important that adults model approaching various passages with excitement, driving a love of reading in their students as they read aloud.

Listen to students read: As students begin reading on their own, they mimic holding a book, turning the pages, and using each page’s pictures to adjust how they read the words aloud (decoded or memorized) to reflect the story in a reasonable manner. Because they’ve observed others read fluently, they try to apply those strategies themselves. It is important to listen to students read aloud in order to support students in reading with appropriate fluency. Fluency assessments (such as measures of oral reading fluency, or ORF) ask students to read a passage as teachers mark errors and calculate the words correct per minute (total words read in one minute – errors = words correct per minute). While using ORF assessments to monitor student progress and inform instruction is valuable, students require ample opportunity to read aloud without it becoming a mechanical task. To support positive feedback and document growth, students must be provided self-reflection scales, partner feedback forms, and fluency rubrics.

Fluency activities: Orton-Gillingham instruction followed by fluency practice at the word level, phrase level, and sentence & passage levels is so critical. When one strives to become skilled in a new activity, one can not immediately participate at the highest or most elite levels. The same applies to evolving as a fluent reader. Extensive reading develops fluency in coordination with skilled word recognition and oral language development alongside listening to reading and reading aloud. Practicing once a day over the course of a week by rereading passages, students improve accuracy and overall fluency.

In the Reading Teacher’s Book of Lists (Fry, Ph.D. & Kress, EdD, 2006), there are several activities to teach and rehearse elements of fluency requiring little to no supplies. For example, in repeated and timed readings, students use the same short passage to improve accuracy and prosody. Pitch (high and low tone of voice), volume (soft or loud voice), speed (fast or slow), and phrasing (short or long pauses between words and groups of words) are all prosodic elements. Students will infer meaning from each of these. A good example of this is when a parent exclaims, “Ah.” The manner in which the “ahh” is stated will change the meaning greatly. “Ah!” implies fear or surprise, while “Ahhhhhh….” relays relief or satisfaction.

Another activity is audio-assisted reading for comprehension of text (from an independent reading level). Students are asked to read along with their books as a fluent reader reads aloud an audiobook. The fluent reader should read anywhere from 80-100 words per minute without having sound effects or music behind their voice. Students will be asked to follow along with the audiobook while having their finger point to the words and help guide their eyes across the page. This should be followed by a rereading of the book where the student reads aloud with the audiobook and should be repeated until the student is able to read the book independently.

A positive outlook on reading is extremely important. Fluency instruction and rehearsal can be engaging and inspiring for students of all ages, especially as they successfully transfer the skills to reading their own preferred texts. For many students, fluency is not only the link but the solution to better reading instruction.

High-frequency words are words that frequently appear in written language and can be either regular (e.g., had) or irregular (e.g., does).

Sight words are words that do not have to be “sounded out” in order to be recalled. In other words, the word is known automatically, is stored in our orthographic lexicon, and can be recalled easily. Sight words can also be regular (e.g., not) or irregular (e.g., my).

The Orton-Gillingham methodology defines Red Words as irregular words that do not follow a particular pattern. Red Words can also be high-frequency words that students must learn before the specific concept has been taught.

Many educators use the term Red Word because the visual color red reminds students that these words are irregular. The Dolch List, Fry Instant Words, and the index of many decodable readers contain lists of these words.

Red Word instruction is an essential part of the Orton-Gillingham approach and should be used on a weekly basis. A large percentage of words that students encounter in their reading and writing are irregular, making it important to include them in daily practice to improve automatic word recollection.

Our brains can recognize familiar words (i.e. sight words) in less than 0.2 seconds. Experienced readers can recognize these words accurately and automatically when reading, making decoding effortless, which improves fluency and comprehension.

Building a student’s sight word bank is a primary goal of research-based instruction like Orton-Gillingham. This provides ample opportunities for review and practice. Some Red Word Essentials include:

Adopting the Orton-Gillingham Methodology

Irregular spelling patterns make Red Words challenging to learn and master. Orton-Gillingham provides a multi-modal approach to Red Word instruction that will activate a student’s learning modalities with the visual, auditory, tactile/kinesthetic feedback essential to promoting long-term memory.

Through Orton-Gillingham instruction, students learn new Red Words in a systematic way, engaging them in steps that integrate gross and fine motor movements, finger tracing, simultaneous verbalization, motor/muscle memory, writing, and short-term memory (digit span memory).

Students gain an advantage in mapping words into long-term memory for automatic recognition if they are introduced to the word parts that contain regular and irregular spelling patterns.

Emphasize Irregularities

When introducing new Red Words during Orton-Gillingham instruction, educators should take the time to analyze the word for irregular spellings. To highlight this, educators should ask the student to identify how many and which sounds they hear in the word.

For example, in the word “was,” the student would begin by identifying the three sounds, /w/-/ŭ/-/z/, by placing tokens to represent each of the sounds in the word. The teacher would then ask the student what letters they would expect to spell each sound.

The teacher will then either confirm or correct the student’s response as the letters are written. The teacher then draws a comparison to sounds that are expected (represented by a matched phoneme in this word, the /w/) or unexpected (irregular spelling in this word, the a represents /ŭ/ and s represents /z/).

It’s recommended for the student to see the unexpected spelling(s) highlighted in red and to count how many irregular spellings the word contains.

This process solidifies the student’s understanding of its Red Word properties and also points out parts of the word where the student can apply phonic decoding knowledge. This step is essential for any student, regardless of age or level.

Categorizing Red Words with Orton-Gillingham

Teachers can integrate high-frequency words into their phonics lessons by carefully examining the various lists of Red Words. This allows students to focus on spelling patterns to enhance their attention to irregularities while recognizing repeated spelling patterns or features of words.

By selecting words for instruction in groups or clusters, you are able to enrich learning and increase the number of words that can be taught in a lesson.

Decodable Red Words should be integrated into the concept lesson whenever possible to piggyback on the student’s knowledge and linguistic vocabulary.

Reading Rockets has identified a variety of categories for Red Word grouping. In addition, many of the Dolch list words have been sorted by spelling patterns for reference and suggestions for effective instruction (readingrockets.org).

Here are a few of the recommended categories from their article:

Concept Matching – As students are learning concepts c-qu and VC, CVC syllables, select words that can be incorporated into the phonics lesson for blending and dictation. Examples include can, not, it, and did.

Known beginning sound – To capitalize on the students’ literacy familiarity, select words that have a beginning sound that has previously been taught. This adds regularity to the Red Word and can help to build a sight word bank early in learning. Examples of words include to, you, for, and I.

Known spelling pattern – Group words by the same vowel sound (i.e. had, ban, am, bat, call contain short /a/), digraphs (i.e. what, then, such), or blends (black, must, sent).

Same vowel spelling pattern – Teach words that share a common vowel spelling in groups, such as he, be, me, we, she (long e), go, no, so (long o), my, fry, why (long i).

Similar spelling patterns – Group words for instruction when they have the same spelling pattern (i.e. could, should, would).

Shared spelling and sound – Cluster words that all contain /z/ spelled with the letter s (i.e. please, hers, as, is).

Build a Base with Orton-Gillingham

Beginning at the start of kindergarten, teachers should introduce Red Word instruction at the onset of Orton-Gillingham instruction and plan to teach high-frequency words that they will regularly encounter in grade-level text.

These words will also complement their concept learning and provide more options for sentence construction and spelling. While there are no absolute conditions for choosing the first dozen Red Words in kindergarten, most teachers are very familiar with the most commonly faced words.

Review and Practice with Orton-Gillingham

The Red Word instructional sequence aims to facilitate and activate memory. The use of Orton-Gillingham’s multisensory approach to introduce pronunciation and spelling combined with repetitive review and practice transfers the information from working memory to storage in our long-term memory.

The review and practice step needs to be considered a crucial part of Red Word learning. Practice definitely makes perfect here!

It is important to educate parents about the multisensory process and the potential outcomes of daily practice since students often review Red Words outside of school.

Learning to both spell the word and read the word is a part of the instructional sequence for teaching a new Red Word. Teachers need to ensure that students have ample opportunities to apply their Red Word learning in both reading and spelling activities throughout the school week. To find activities to promote Red Word review and practice, go to https://www.pinterest.com/ortongillingham/red-words/.

Multi-sensory instruction, such as Orton-Gillingham, typically refers to visual, auditory, and tactile/kinesthetic pathways (VATK).

According to the research of Dr. Samuel Orton, strengths or preferences will vary from student to student but using more than one method will help students better retain information.

3 Components of Multi-Sensory Instruction

Multi-sensory instruction can be broken down into these three components:

- Visual Learning

- Auditory Learning

- Tactile/Kinesthetic Learning

The most critical aspect of multi-sensory instruction, such as Orton-Gillingham, is having students use more than one of their senses. The most effective strategy for children with difficulties learning to read has proven to be using multi-sensory techniques.

However, multi-sensory instruction is not just for students that have learning disabilities. According to The Ladder of Reading (Nancy Young, 2017), only 40% of learners can learn to read effortlessly or with relative ease and comprehensive instruction. That leaves 60% of all learners to benefit from instruction like Orton-Gillingham.

Orton-Gillingham helps you to tap into your students’ sensory learning pathways. That’s why multi-sensory learning and explicit instruction are the most concrete methods for teaching a new concept.

Multi-Sensory Instruction: Visual Learning

When we think about the visual component, we think about the sense of sight. Students should see visuals that represent the meaning of what is being taught.

Showing written-out directions is an example of a visual modality. Teachers can provide students with handouts, a slideshow, or other visual aids to help them follow along during a lesson.

Other visual aids include:

- Charts

- Flashcards

- Graphs

- Diagrams

- Lists

- Maps

- Pictures

- Visual cues

- Written summaries

Multi-Sensory Instruction: Auditory Learning

When we think about the auditory component, we think about the sense of hearing. Students should hear the explanation of directions out loud.

Lesson plans should include social elements like:

- Paired reading

- Group work

- Experiments

- Projects

- Performances

- Oral reports

- Lectures

- Mnemonic devices

Rhymes, beats, or songs can reinforce information. Providing recordings of lessons can also be beneficial, so students can go back and listen to the lesson more than once.

Multi-Sensory Instruction: Kinesthetic/Tactile Learning

When we think about the tactile and kinesthetic components, we think about the sense of movement and touch. Tactile instruction incorporates using hands to do something, such as manipulating objects representing a concept. Kinesthetic instruction involves moving to focus and learn.

The main difference between the two strategies is tactile components focus on fine motor movements while kinesthetic components focus on whole-body movements. So, while arm tapping would be a kinesthetic strategy, finger tapping is a tactile strategy.

Methods that support kinesthetic and tactile instruction include:

- Providing hands-on tools

- Giving breaks to allow students to move around

- Using the outdoors

- Teaching concepts through games and projects

Even if you’ve already taught a lesson using auditory and visual elements, it can be highly beneficial to reinforce that information through dance, play, or other activities.

Additional Activities for Multi-Sensory Instruction

Phonogram Review: Review sound-symbol correspondence with a rapid phonogram card drill

Simultaneous Oral Spelling: Repeat words, sound or spell words out using finger tapping, write words while saying letters, and read the completed word

Reading Words: Read a series of words and sentences that use the new pattern, as well as review words targeting skills that need particular practice

Everyone Benefits From Multi-Sensory Instruction

Our brains have developed to learn and grow in a multi-sensory environment. When teachers and educators introduce new material using multisensory learning, like Orton-Gillingham, they effectively cater to a more expansive audience of learners.

Multi-sensory instruction is used to teach all students effectively, especially those with learning differences. By using multiple senses, all learners have more ways to connect with what’s being taught.

“Reading and writing have been thought of as opposites – with reading regarded as receptive and writing regarded as productive. Researchers have found that reading and writing are ‘essentially the same process of meaning construction’ and that readers and writers share a surprising number of characteristics” (Carol Booth Olson, 2003).

The Orton-Gillingham methodology supports progress toward mastery of reading, writing, and spelling as one body through the explicit instruction of encoding and decoding strategies.

Is Explicit Reading & Writing Instruction Necessary?

Speaking, otherwise referred to as an oral language, is a more natural process in human development, whereas reading and writing, referred to as written language, must be taught.

Seeking opportunities for incremental success through Orton-Gillingham instruction proves incredibly motivating for students who find learning to read, write, and spell challenging. This is especially true for EL students and individuals with learning disabilities.

It’s easy to dismiss something when it is challenging to learn. “Is this really necessary?” or “I can make it without knowing bigger words because I already know a basic word which means the same thing.”

We should always push students to continue their literacy journey towards being proficient readers, writers, and spellers.

Encoding

Spelling is essential when completing job applications, establishing credibility as a writer, using a literal or online dictionary, or recognizing the best choice when using spell check (Liuzzo, 2020).

According to Marcia Henry (Unlocking Literacy, 2004), to be an accurate reader and speller, one must have knowledge of:

- Phonology: the study of sounds

- Orthography: the study of writing systems and sound-letter correspondences

- Morphology: the study of word parts that shape word meaning

- Etymology: the study of the history of words

Peter Bowers (2009) states, “Explicit instruction about the role of phonology and etymology is not optional if we accept the challenge of offering students accurate, comprehensive instruction.”

“The development of automatic word recognition depends on intact, proficient phoneme awareness, knowledge of sound-symbol (phoneme-grapheme) correspondences, recognition of print patterns such as recurring letter sequences and syllable spellings, and recognition of meaningful parts of words (morphemes)” (Moats, 2020) and (Ehri, 2014).

As students use phonology, orthography, and morphology to identify how to spell words, the knowledge of spelling patterns and rules knit together the layers of the English language. For example, understanding why suffix -ed makes each of its three sounds, /id/, /d/, or /t/, hinges on determining the final sound of the base word. Students must first hear the past tense verb and isolate the base word.

In the past tense verb asked, the base word is ask, which ends in the unvoiced sound /k/. Therefore, in the past tense verb asked, the suffix -ed will make its unvoiced sound /t/. As the student encodes the word, they must apply their knowledge, as, “I hear /t/, but I write -ed.” Ensuring mastery of phonological awareness skills as a foundation upon which students build phonetic knowledge is critical.

A fluent writer is born when the students’ segments to spell the phonemes in monosyllabic and polysyllabic words with increasing automaticity.

Decoding (de / co / ding)

In Reading Reasons, Gallagher notes many ways reading is valuable, including building a mature vocabulary, making you a better writer, more intelligent, providing financial rewards, and helping develop your moral compass while arming you against oppression.

Beginning readers can become intimidated by long words. However, Orton-Gillingham instruction teaches these readers that they can decode or “break the code” to tackle the increasingly complex patterns.

Decoding these words causes the students to broaden their vocabulary, a critical piece to better writing and deeper comprehension. The knowledge of syllable patterns and syllable types increases students’ ability to sound out unfamiliar phonetic words.

“If reading skill is developing successfully, word recognition gradually becomes so fast that it seems as if we are reading “by sight.” The path to that end, however, requires knowing how print represents sounds, syllables, and meaningful word parts; for most students, developing that body of knowledge requires explicit instruction and practice over several grades” (Moats, 2020) and (Ehri et al., 2001).

To apply decoding strategies, students employ knowledge of individual phoneme/grapheme relationships, including identifying vowels and consonants. Next, they discover the syllable division pattern(s), which indicates how to cut the word into syllables. Then, students look at each syllable and determine the syllable type, which indicates how to pronounce the vowel sounds.

There are four-syllable division patterns in English listed by frequency:

- VC/CV (harbor)

- V/CV (heaven)

- VC/V (cabin)

- CV/VC (labor)

There are seven syllable types in English:

- Closed syllables (hat)

- Open syllables (to)

- Magic-e syllables (bake)

- Vowel team syllables (heat)

- Bossy r syllables (curb)

- Diphthong syllables (howl)

- Consonant-le syllables (bubble)

Eventually, these techniques are systematically applied to phonetic multisyllabic words in a multi-sensory method to read the entire word. Over time, the brain develops automaticity (fast, accurate, and effortless word identification at the word level) and fluency (automatic word recognition plus the use of appropriate prosodic features of rhythm, intonation, and phrasing at the phrase, sentence, and text levels) to decode and comprehend efficiently.

Irregular Words

A small percentage of English is always irregular. However, irregular words will vary from student to student based on the phonetic concepts learned. Sounds used to pronounce these irregular words are not as clearly linked to their spelling. Therefore, students must memorize the letter strings to spell and read the words.

The words become recognizable on sight once they are memorized and orthographically mapped in the brain. Students observe the order of the letters and state the word. Understanding the impacts of morphology and etymology helps students bridge the gap between the expected and unexpected letters in irregular words.

What Should We Read?

Decodable books contain roughly 80% decodable text, leaving only 20% of words irregular or recognizable on sight. Controlled, decodable readers follow a sequence of instructions, allowing students to apply decoding strategies independently. Decodable texts provide motivation and encouragement for developing readers.

These texts encourage students to layer strategies to become strong readers when they are partnered with fluency instruction. Even when one has the capability to read, they choose not to. Why is it that some students not find reading rewarding?

When reading books or passages at a frustration level, students spend too much time and mental effort on decoding at the word level, leaving little room for fluency and understanding. Decodable texts provide opportunities for the application of learned skills. This is empowering to students – and empowered readers become naturally motivated.

The development of decoding skills must be accompanied by fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies. Decodable poems are naturally phrase-cued texts which encourage students to group words into meaningful phrases. When purposeful illustrations accompany texts, it supports the development of visual imagery linked to deeper meaning. Similarly, decodable passages and books with illustrations serve as stepping stones toward chapter books.

Inspire Readers & Writers

Irregular words and phonetic words have the opportunity to become sight words, which is the goal of explicit instruction like Orton-Gillingham – students’ brains function so proficiently, allowing cognitive functions to focus on fluency and comprehension. Ultimately, explicit, systematic, cumulative, multi-sensory instruction in encoding and decoding phonetic and irregular words inspires and encourages readers and writers.

Syllabication and decoding strategies can provide the keys to reading and the road map to navigating increasingly complex and engaging texts. Syllabication is the process of dividing words into syllables while decoding is the ability to utilize letter-sound relationships to pronounce those words. These a some of the strategies learned through the Orton-Gillingham methodology. Orton-Gillingham is a step-by-step learning process involving letters and sounds that encourages students to advance upon each smaller manageable skill learned throughout the process.

To decode phonetic words, readers need prior knowledge of the individual syllable types, perhaps taught in monosyllabic (single-syllable words) prior to reading them in longer words. As readers approach an unfamiliar multisyllabic phonetic word, they may apply strategies to break the longer word into manageable chunks, called syllables. Syllable division patterns guide readers in this process and they’re taught in order of their frequency of use in English. Once words are cut into syllables, the six syllable types will help readers identify how to pronounce each syllable.

Syllable Types:

Syllable Type 1: Closed

A closed syllable contains a single short vowel closed in by a consonant in the same syllable. These syllables are extremely common in English, and the short vowel sounds are the first vowels taught. In words, such as cat, dog, red, and cup, the vowel is closed in and, therefore, is pronounced with a short vowel.

Syllable Type 2: Open

An open syllable is when the single vowel stands alone and occurs at the end of a syllable. Every single vowel in English says its name in an open syllable, as in go, hi, we, and she.

Syllable Type 3: Magic E (VCe)

Magic E is a silent “e” that magically empowers the preceding single vowel to say its name. In words like bike, pole, cute, and bathe, the Magic E jumps back over a consonant sound, and the word (or syllable) is pronounced with a long vowel sound.

Syllable Type 4: Vowel Teams

A vowel team is a vowel sound represented by two to four letters, including ‘ea’ as /ē/ in meat (long vowel sound E) or /ĕ/ in bread (short vowel sound e), ‘ow’ as /ō/ in grow (long vowel sound O) or /ow/ in town (a diphthong vowel sound), or “igh” as /ī/ in night (long vowel sound I). Teachers empower students to efficiently read and spell by introducing the most common vowel teams first, such as the six VTs which spell long vowel sounds: ea, ee, ai, ay, oa, & oe. Then, once students demonstrate mastery, teachers may introduce additional vowel teams.

It is imperative that teachers continually discuss how to articulate phonemes (sounds) because vowel teams can spell long vowel sounds, short vowel sounds, and most diphthong vowel sounds. A diphthong (Greek for “two sounds”) is a gliding monosyllabic vowel sound, and students may feel the diphthong’s gliding movement by placing their fingers on the cheek next to the corners of their mouth to feel the slight muscle “glide” as they say the sound, like /ow/ as heard in out. Some programs pull out diphthongs as an additional syllable type.

Syllable Type 5: Bossy R

When an “r” follows a vowel sound, as in verb or far, it attempts to control the preceding vowel’s sound. In doing so, readers and spellers encounter an entirely new vowel sound. Teachers must clarify the sound of the “r” in isolation compared with the bossy r, or r-controlled, vowel sounds.

Syllable Type 6: Consonant-le

The final syllable type, consonant-le, occurs at the ends of words in English. Because every syllable has a vowel sound, the silent e at the end of this syllable signals readers to its pronunciation. For example, when table is enunciated, the -ble syllable may be reflected as /b(ǝ)l/ with an unpronounced schwa vowel sound. When reading a word that ends in a consonant-le syllable, readers may circle the syllable.

Syllable Patterns:

Syllable Pattern #1 VC/CV

The most common syllable division pattern is recognized by two or more consonants between two vowel sounds, including VCCV, VCCCV, VCCCCV. Consider the following words:

- parrot – The two vowels are ‘a’ and ‘o’, and there are two consonants between the vowels. Pattern #1 cuts the word apart as par / rot.

- hundred – The two vowels, ‘u’ and ‘e’, have three consonants between them. Pattern #1 cuts the word apart as hun / dred.

- construct – The two vowels, ‘o’ and ‘u’, have four consonants between them. Pattern #1 cuts the words apart as con / struct.

Syllable Pattern #2 V/CV

The second most common syllable division pattern is recognized by VCV, with only one consonant between two vowel sounds in a word. Because of its frequency in English multisyllabic words, when readers encounter a VCV pattern, this pattern directs them to cut the word apart after the first vowel. Consider the following word:

- final – The two vowels, ‘i’ and ‘a’, have one consonant between them. Pattern #2 cuts the words apart as fi / nal.

Syllable Pattern #3 VC/V

Readers may attempt to read a word using pattern #2 and not recognize it in their oral language lexicon. When pattern #2 doesn’t result in a familiar word, perhaps something else is happening. Often, the “something else”, is pattern #3 where the word cuts apart after the consonant between the two vowel sounds. This pattern is the second choice because, in English, it’s less common. Therefore, readers should have ample opportunity to apply patterns #1 and #2 before this pattern is introduced. Consider the following word:

- salad – The two vowels, ‘a’ and ‘a’, have one consonant between them, so the reader tries pattern #2, initially, and reads sa / lad. While searching for words known in their oral language and prior listening, reading, and speaking experiences, the word doesn’t make sense. Then, the reader suspects pattern #3 could be at work, and they adjust how the word is cut apart and reads sal / ad.

Syllable Pattern #4 V/V

This final pattern used to cut words apart in English has two vowels with no consonants between them, and it is the least common of the four patterns. Typically introduced once diphthong vowels sounds are taught, readers continue to test the pattern and resulting pronunciation against known words in their oral language. Consider the following words:

- science – The two vowels (vowel sounds), ‘i’ and ‘en’, do not have any consonant sounds between them, and the reader cuts pattern 4 and reads sci / ence.

- gradual – The first two syllables cut apart using pattern #2, and the second and third syllables cut apart using pattern 4. The reader decodes gra / du / al.

Once syllable division patterns (ways to cut words apart) and syllable types (guides to pronunciation) are learned, it’s as if every reader has the map to discover reading longer phonetic words. When syllabication strategies are applied more skillfully and automatically, the landscape of reading is widened, varied, and accessible. Readers are able to focus on fluency strategies and vocabulary which support reading comprehension.